KVIFF Interview: Juho Kuosmanen on his Silent Trilogy

"The grammar of silent films gives me freedom that I don't feel that I have with feature films."

You may know Finnish filmmaker Juho Kuosmanen from his debut film The Happiest Day in the Life of Olli Mäki, which was screened as part of Un Certain Regard at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival, his follow-up film Compartment No. 6, which shared the Cannes Grand Prix with Asghar Farhadi's A Hero at the 2021 edition of that festival, or from his recent television series Alice & Jack. But if you’ve been at either this year’s Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival in Bologna, Italy or the Karlovy Vary International Film Festival in the Czech Republic, then you probably know him from his playful and irreverent silent film trilogy.

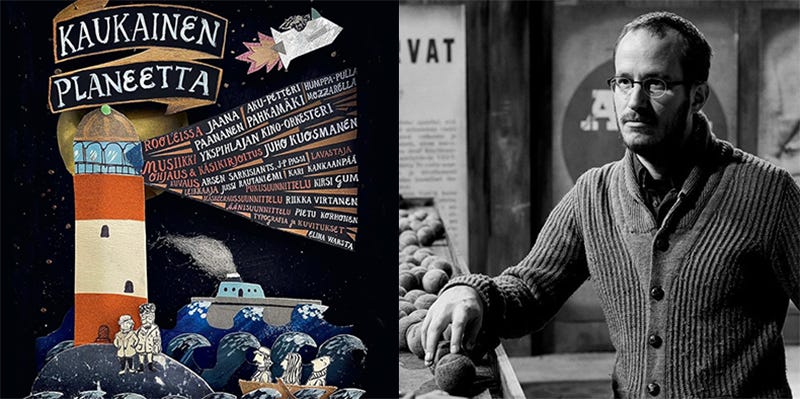

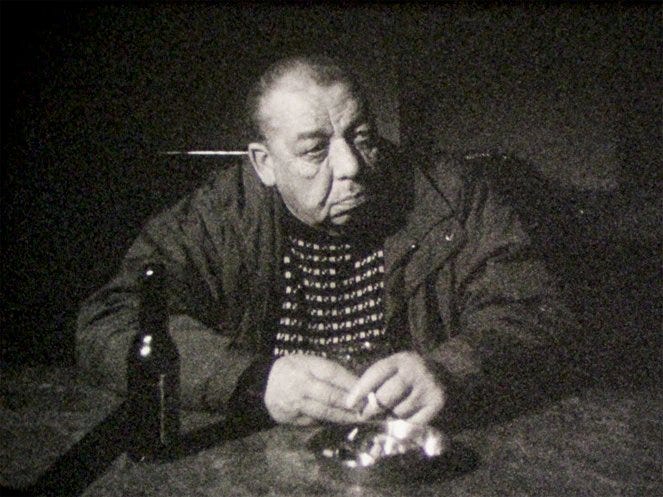

The first film in the trilogy, Romu-Mattila ja kaunis nainen (Scrap-Mattila and the Beautiful Woman) (2012), started out as a lark made with friends as Kuosmanen prepared to make his first feature film. However, when non-actor Seppo Mattila was cast in the lead, the film took on a grander purpose. His second film, The Salaviinanpolttajat (The Moonshiners) (2017), is a fanciful remake of Finland’s very first silent film to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the country and the 110th anniversary of the original film. Like many films from the early cinema era, the original film was lost, so Kuosmanen and co. interpreted the screen story with their own brand of wit and humor. You may, like me, have seen the film when it was screening on the Criterion Channel a few years back. Wanting to give the films a proper ending, Kuosmanen re-teamed with his constant on screen partner Jaana Paananen for the final film in the trilogy, Kaukainen planeetta (A Planet Far Away) (2023), a wry and sweet space adventure that is also a loving tribute to siblinghood.

I was lucky enough to sit down with Kuosmanen at KVIFF to talk with him about the making of his trilogy, our shared love of silent films, and the freedom he finds working within silent film grammar. Read our full conversation below.

It’s always fun to see silent films with an audience who are not used to silent films but are engaging with them how they were intended. Were you sitting through and watching with the audience?

No, no, this time, I wasn't. I watched them in Bologna [at the Il Cinema Ritrovato Festival].

Did they engage really well there as well?

Yeah.

There was some howling laughter for The Moonshiners.

Perfect.

People loved it. It was really fun. I wanted to ask you to start with, obviously, as you know, there aren't that many people who really love silent films these days. How did you first get into loving the era?

I think the problem is that people haven't seen silent films.

Exactly.

They haven't seen silent films especially with the live music, the way they were meant to be screened. I think that is really a crucial element.

Agreed.

When doing this, the first idea was that, okay, they have to be screened only with a band, and then with the first two, we also had a live foley artist, and we screened them with my 16mm projector. I felt like this is the thing; it's not just the films.

Yeah, it's a whole experience.

I'm happy they also work without the live element. When you watch silent films, like on the TV, it's just not. . .it's not fair to them. I love them because, well, generally, I love films. I love old films. But I also go to Midnight Sun Film Festival, and they have a great selection of silent films with different kinds of soundtracks. So I think that's where I actually saw silent films for the first time that I felt like, okay, this is how it should be.

Have you ever made it to the Pordenone Silent Film Festival in Italy?

No.

I think you would love it. I've gone a few times. It's really something. I haven't made it to Bologna yet.

Bologna is also incredible.

So you shot the first two films on a Bolex, right? What did you shoot this third one on? I didn't see it in the credits.

It's also shot partly with a Bolex, but we started to shoot it with a 35mm camera, an old Arriflex, and there are a couple of shots done with an iPhone.

Really?

Yeah.

It's very seamless in that third one. When I went to film school, they made us make films on a Bolex and edit it with a Steenbeck. I saw you edited the first two films with a Steenbeck. I love how, especially in the first film, it feels like a film that maybe was in a can for 100 years and then found and projected. How did you add that noise? Did you hand scratch it or was that part of the digitization of it?

No, I think it was just the fact that the film, after being shot with Bolex, you know, it gets some scratches and some dust on it, and then while working, putting it on clips working on the Steenbeck, it gets a bit of damage. Then when we had the final film, and at first, we only screened it with that original film print, but when the film print started to be in a quite bad condition, we decided to scan it. So it had already gone through the Bolex, It had gone through the Steenbeck several times, and it had gone through my 16mm projector several times.

So that's earned scratches.

Yeah. And actually, there was a moment when we showed it in St. Petersburg in Russia and my projector was broken and the part that collects the reels didn't work, so all the material went to the floor.

Oh no.

And then after the screening, I saw that and the interpreter of the intertitles was kind of stepping on it.

That's one of the perils, I guess, of working with film. Those 16mm projectors are not always the easiest.

Yeah. It's fun to have the projector in the middle of the room.

And you hear that sound and kind of feel the heat a little bit.

Yeah.

That's really cool. I love the story you told in the intro about how you started the first film as a comedy, and some of that is still there, but then it ends up very melancholic, which I think is true to a lot of silent comedies. They have a real melancholy to them. Was that something you found as you were filming or as you were editing?

Already while filming or even while prepping. It was a matter of the cast. Casting is always the biggest thing a director can do. Then it's like, okay, you hope for the best. In this case, because it was his story, with his presence, the way he looks. I mean, it was all quite powerful. Then after meeting him for the first time, I was driving back to Helsinki with my DOP, and I said, "Okay, this is, you know, it's not light weight anymore." We realized it was getting serious and it should be treated with, not seriously, but with the respect of him, of his character. We can't laugh at his circumstances. Respect, though, it's not the perfect word, but I can't find any other one at the moment. We wanted not to be serious, but not to fool around with his story. I mean, we could still fool around with the idea of making a film, but the story was not something to laugh at.

One of the things I liked in all three of the films was the way you have a juxtaposition between very old timey things, and then, you know, it's clearly not an old timey film. Like there's a car going by when they're driving the moonshine cart. They talk about GPS, but then she has that old school radio. How did you balance the humor of adding just a little bit of modern touches to the films?

Those elements are there because I wanted to make it clear, like, okay, these are done now. With the first one, there are also some elements, like, there's the Visa Electron mentioned.

That was funny. People laughed. They laughed really hard.

I also wanted to say to people who are like "The period is not right," I wanted to say, like, "Fuck you."

That's funny.

We are not trying to be somewhere. We are in this time. It's just the way, you know, we do this thing. And it was also to give this freedom to the audience. It's not a film that is made by the rules or kind of trying to be something.

I love how playful these films are. I think part of the reason I love the silent era, as someone who's watched a lot, is that most of those films are very playful, especially the films from the teens, because they're trying stuff, right? I think for people who don't watch a lot of silent films, they maybe think they're either just the serious ones, or maybe they're just Buster Keaton, and there's nothing in between. I love that these films celebrate how weird early cinema is.

Yes, and just doing things for fun, which was pretty much the case with these films. I also would like to add, what you said about silent films, people have the idea that there's a certain kind of elitism about it. And it was never the case. Film was made for street level people. It's not anything like high art. And so you can see in the early days, when people are just fooling around with a water wheel and the slapstick stuff. They're like children making enjoyable and playful stuff. And there's also a huge variety of kinds of films.

Have you watched a lot of the Scandinavian silent era, like not just from Finland, but from Sweden and Norway?

Yeah, I think more Swedish than Finnish. There are not many Finnish silent films.

I've seen, like, two. But I’ve seen a lot from Sweden and Norway, and there's a lot in Denmark. The Danish Film Institute has digitized every single extant Danish silent film.

In Denmark, they have the oldest studio in Europe. It's kind of a museum now, but it's still there. Denmark and Sweden have been like major countries for films for years. And Finland has not many. We've been much more into music.

Contemporary Finnish cinema, though, I feel like I've seen every year, three or four that have broken through in America that I've really loved, of every genre. Girl Picture is a teen movie, then there's a horror film like Hatching, a rom-com like Fallen Leaves, and then a drama like your film Compartment No. 6.

It's getting more international. I'm getting more known.

It’s kind of a small community. Do you know all the filmmakers?

Yeah, it's a small community. Also the film culture itself is totally different than in Sweden or in Denmark. It has been much more homemade stuff that we've done.

It feels homemade in a really, like genuine way.

The best ones might be the ones who are trying too much [laughs].

I haven't seen a Finnish film that I have disliked so far. I wanted to ask, not just in terms of Scandinavian silent films, but do you have some favorites from the era? It's a long era that spans forty years, but do you have a film that maybe you return to or that you love looking at for inspiration?

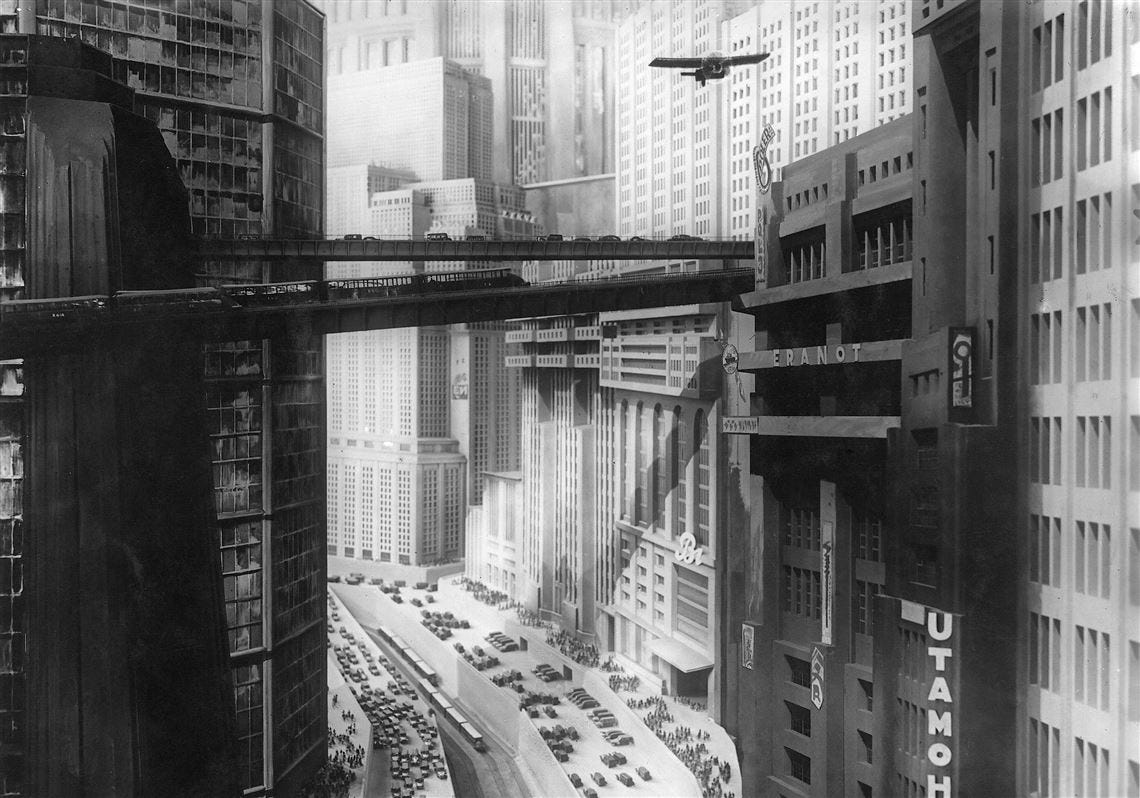

It's a hard question, and coming back to where we began, there are some screenings that are really memorable that I really have enjoyed. One was Buster Keaton's Our Hospitality. I saw it in Paris. It was my first trip to Paris to watch films and then I remember, I cycled there with a City Bike of Paris on a Sunday morning. It was a nice screening with a pianist. I enjoyed it a lot. I was just so in love with cinema after that screening. Then, well, there's films like Sunrise, which is obviously a masterpiece, even though the morality is old fashioned. And of course Metropolis.

I think that was the first silent film I ever saw. It was one of my dad's favorite films.

After Metropolis it's pretty much downhill [laughs]. But I love those films. I think it's also a matter of where you saw it, you know, in what kind of cinema, in what kind of room, and what was the overall feeling. And also the soundtrack. Was it bad? Because I've seen, like with Metropolis, I've seen with many different screenings. I've seen it with a recorded soundtrack, and then I've seen it with a couple of different live soundtracks, and it's still the same film, but the experience is very different.

A lot of times I'll watch silent films, either on TCM or maybe on YouTube or something, and the score is terrible, so I'll turn it down and put a different score on.

I've also had the same feelings where I'm like, I can't bear this score. There was a collection of Chaplin shorts, and they were playing with this pretty bad Dixieland music. They were just playing and they were fooling too much and they were not, it was not connected with what was happening on the screen. It was like, fuck this, you didn't even try?

Yeah, it can really change the experience. You said that the third film is your ending to this trilogy. Do you think you'll make other silent films for fun?

I think I will, yeah.

Do you think you'll connect them again? Or is that something that just kind of happens as it happens?

It's like, let's see. I have some ideas. After the screening at Ritrovato, I had a nice talk with Alice Rohrwacher and Gianluca Farinelli about the future of silent cinema and then I started to feel like I never felt that way, even these films, they were not meant to be shown. I mean, they are made with friends, the people who are acting in them, they are not actors, they are my friends, people that I know. But now that they seem to work, they are not finding a big, big audience, but still a bit of audience. So, for the past few days, I've been thinking like, okay, why not? Because it's a really nice form. It also, for certain ideas, might actually be a better form than the basic sound movie.

I did a podcast a couple of weeks ago that was all about my favorite films from 1924 and I was trying to describe one of the films, and I couldn't. I just didn't have the words because this is literally a visual film. I can't even tell you why it's good. You just need to watch it. Trust me. I think that's kind of–

The best experiences are like that.

Yeah, there's just no words. Also, I wanted to tell you, the guy sitting next to me during the screening, he was so enamored with the third film he kept trying to take pictures of the stars with his phone camera. I wanted to tell him to stop, but on the other hand, I was like, he's so engaged. It was really adorable.

That was actually shot with my iPhone. I was shooting a glass of sparkling water.

Oh, wow.

And the bubbles looked like stars.

He was impressed, that guy. My last question could describe what it is you love about silent films? I know it's a really hard question. I can never do it, so this is a very hard question and I apologize. But can you maybe distill down why you love them and why you continue to return to them?

Why I like to watch them, I can't answer.

That's the hard one.

It's like somebody said, if you can describe why you love some person, the love is destroyed.

Exactly, yes.

So I don't even want to try. But why do I enjoy making them? I think it's because the grammar of silent films gives me freedom that I don't feel that I have with feature films. And it's not about if financiers or anybody says something to me, but it's more about my own limitations. When I do normal feature films I'm really limited by the fact that I want it to feel real. I want the complexity of human relationships and all that kind of stuff. And in silent films, I feel I can be more melodramatic. I don't have to be real with emotions or anything. I can be black and white. I can be this and that. And I really enjoy it. You don't have to be subtle. You don't have to be somewhere in this folky, ambivalent ground. You can be like, okay, let's be sad and let's be funny.

I think I can't call it freedom, because it's not freedom, because it's limited. But I think that the fact that you have clear choices that you have to make. Also, working with that Bolex, it's like, okay, we have 30 seconds. So what can we do? We have two, three lenses. So what can we do? All these choices are kind of easy. Also the fact that only the last one had a budget, like a real budget. The first two are, especially the first one, done with almost zero money.

What could I call it? I've been calling it freedom, that it's giving me freedom to do ba-da-ba, but actually, it's not about freedom, because it's limitations. Maybe I enjoy the fact that I'm forced to make these choices and not to be burned by ambivalence and subtle stuff and all that realism. It's like fairy tales, like telling fairy tales. When you have a happy ending, you don't have the question, “but does life?”