Your Silent Face: John Gilbert

Periodical Ruminations on Silent Film Stars, Summer Under The Stars Edition

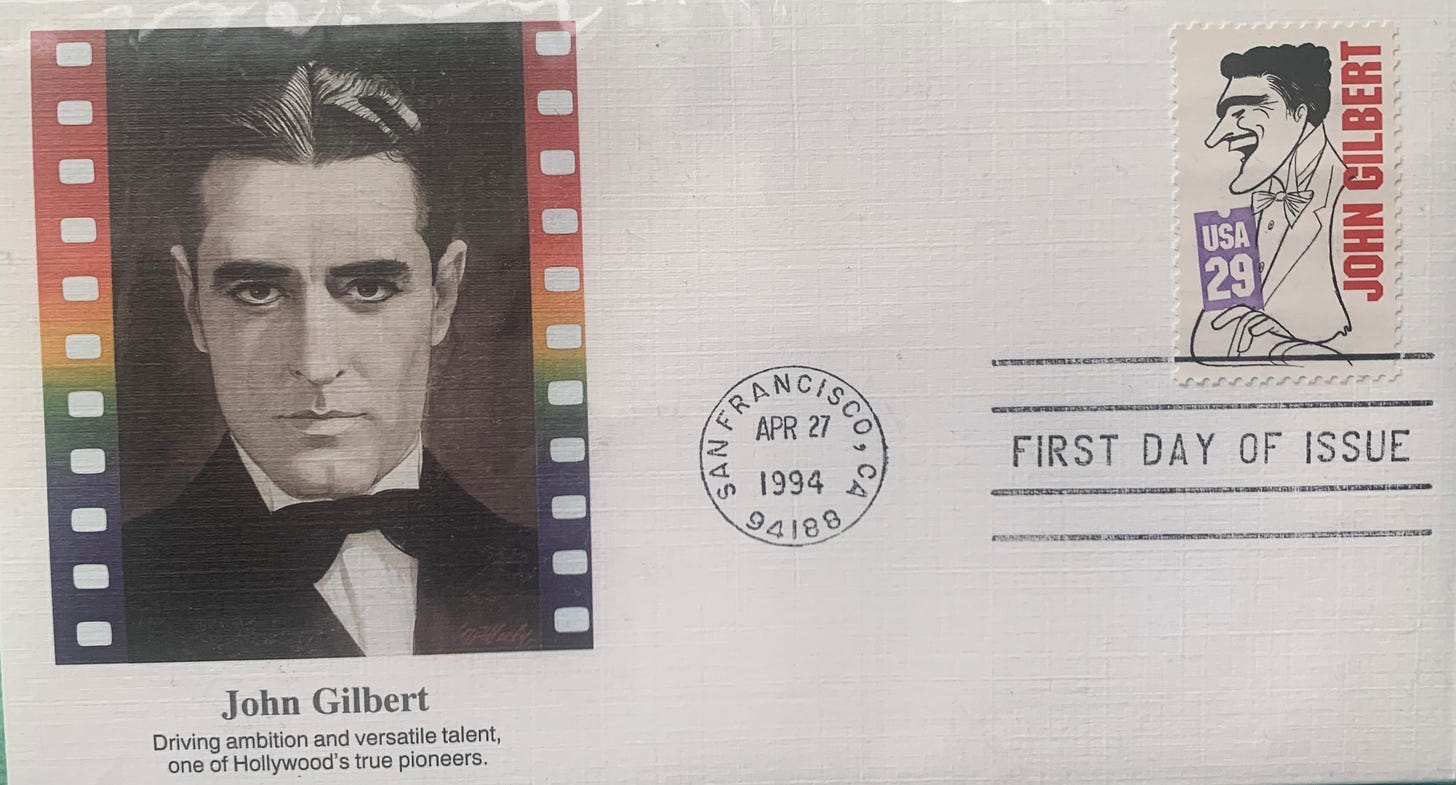

That’s right I am finally bringing this feature back! When I launched it last year with a profile of Mary Astor I fully intended to make it a semi-regular thing. Then life got in the way. But, because today is John Gilbert day on TCM’s Summer Under The Stars, I knew it was time once again. Jack is probably my favorite silent film star. I know that is saying a lot, but I mean it. I just find him so beguiling and I want more people to love him too!

If you are a fan of Babylon (or maybe even if you hate Babylon), you might be fairly familiar with some of the beats of Gilbert’s life (and also some of the myths). When I interviewed Damien Chazelle about the film I asked him how John Gilbert became one the major inspirations for Brad Pitt’s character Jack Conrad.

Here’s a bit of what he told me:

I love that you say that he's one of your favorite actors, because I feel like that's, again, one of these weird things, where the story or the urban legend or whatever, has kind of replaced the reality. What fascinated me with John Gilbert was ... so to be honest, early on before I didn’t know much about John Gilbert, I had in my mind the idea of a character who was the King of Hollywood character in the silent era, but who had a voice where it was a little bit like a male version of like Jean Hagen in Singin’ in the Rain. It was a voice where you knew right away oh, well, they're going to be fucked when sound comes. That was a little bit of the idea I had in my head of what the John Gilbert situation was. That he had this high-pitched voice that the audience laughed at. And when sound came, he was done for.

But it was so much more interesting actually, the reality.

Last summer I wrote about Jeanine Basinger’s book Silent Stars, in which she perfectly distilled what I love so much about him:

He faced the lens without fear, and he knew how to smolder. He projected the image of a handsome, passionate, somewhat brooding man, but at the same time he seemed real, tangible. He was not exotic and remote, a dream man you were never going to meet in your ordinary life, like Valentino. Meeting John Gilbert might be a stretch, but it seemed possible.

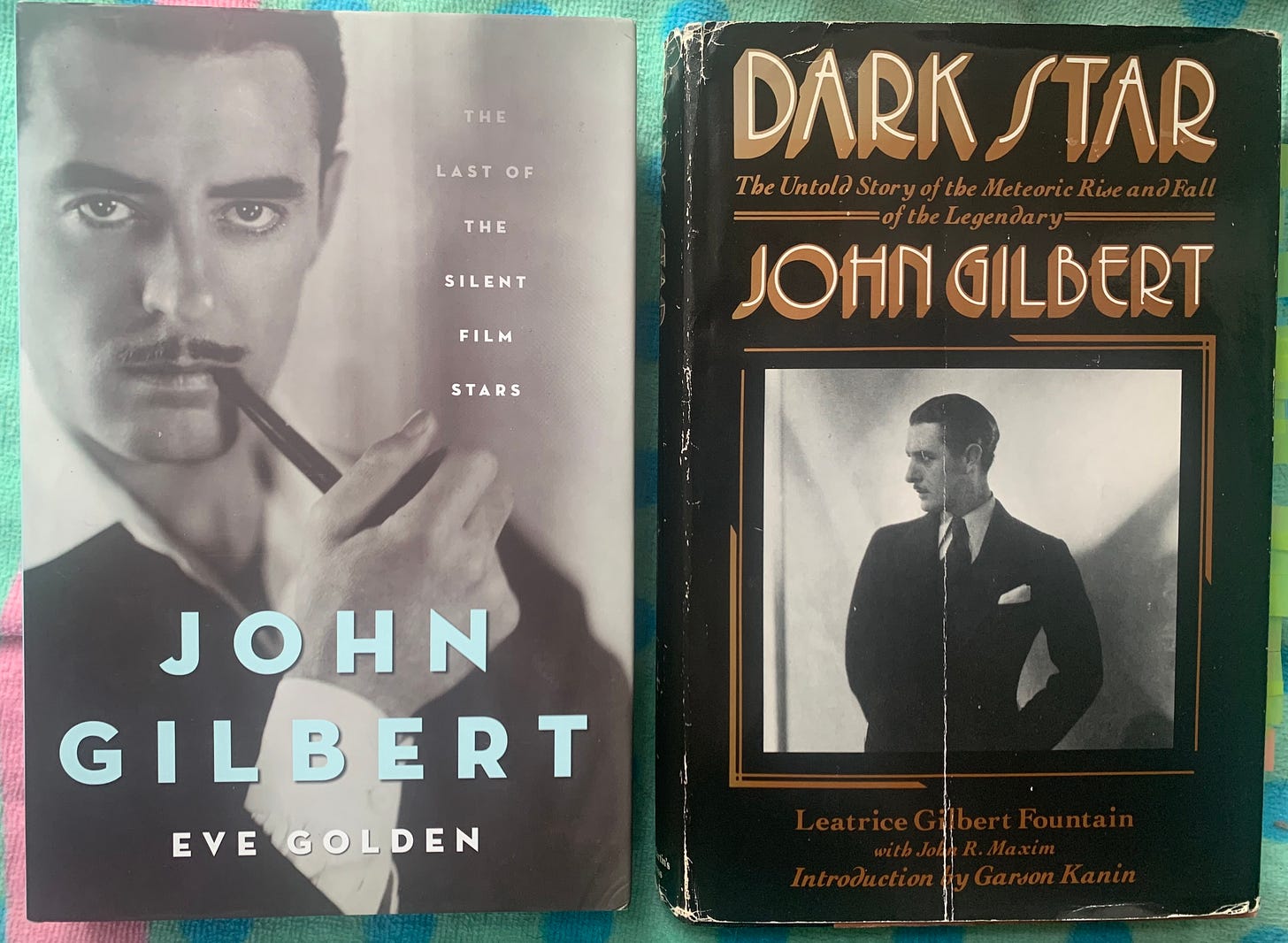

Last year I also read Eve Golden’s biography of Jack, which was well researched but is often overwhelmed by Golden’s snarky voice. A couple of weeks ago I finally tracked down a copy of Dark Star: The Untold Story of the Meteoric Rise and Fall of the Legendary John Gilbert, the biography written several decades earlier by Jack’s daughter Leatrice Gilbert Fountain. I found this book to be much more compelling, not just because of Fountain’s personal connection to the material, but because her way of relaying anecdotes was much more eloquently written. The book begins with an introduction by Garson Kanin, which also contains a great description of Jack:

He was the epitome of dashing, daring, glamorous action — the quintessential Movie Star, the role model for a generation of would-be lovers. . .Those piercing dark eyes that not only looked, but saw. That dazzling smile which disarmed and conquered. The incomparable physical grace and aesthetic elegance.

Fountain traces her father’s life history, from his birth in Logan, Utah to his life with his itinerant actress mother Ida Adair to his ascension to Hollywood royalty. Fountain uses a four-part autobiography that Jack wrote for Photoplay, which you can still read thanks to Lantern, as a jumping off point, filling in gaps with her own research, including interviews she conducted with several people who knew him in his prime, like her own mother, Jack’s second wife Leatrice Joy. The details she unearths are often shocking and sad, a childhood filled with emotional and physical neglect. These details explain the great well of emotion he was able to translate on to the big screen, as well as the generous and giving spirit he was known for throughout his time in Hollywood.

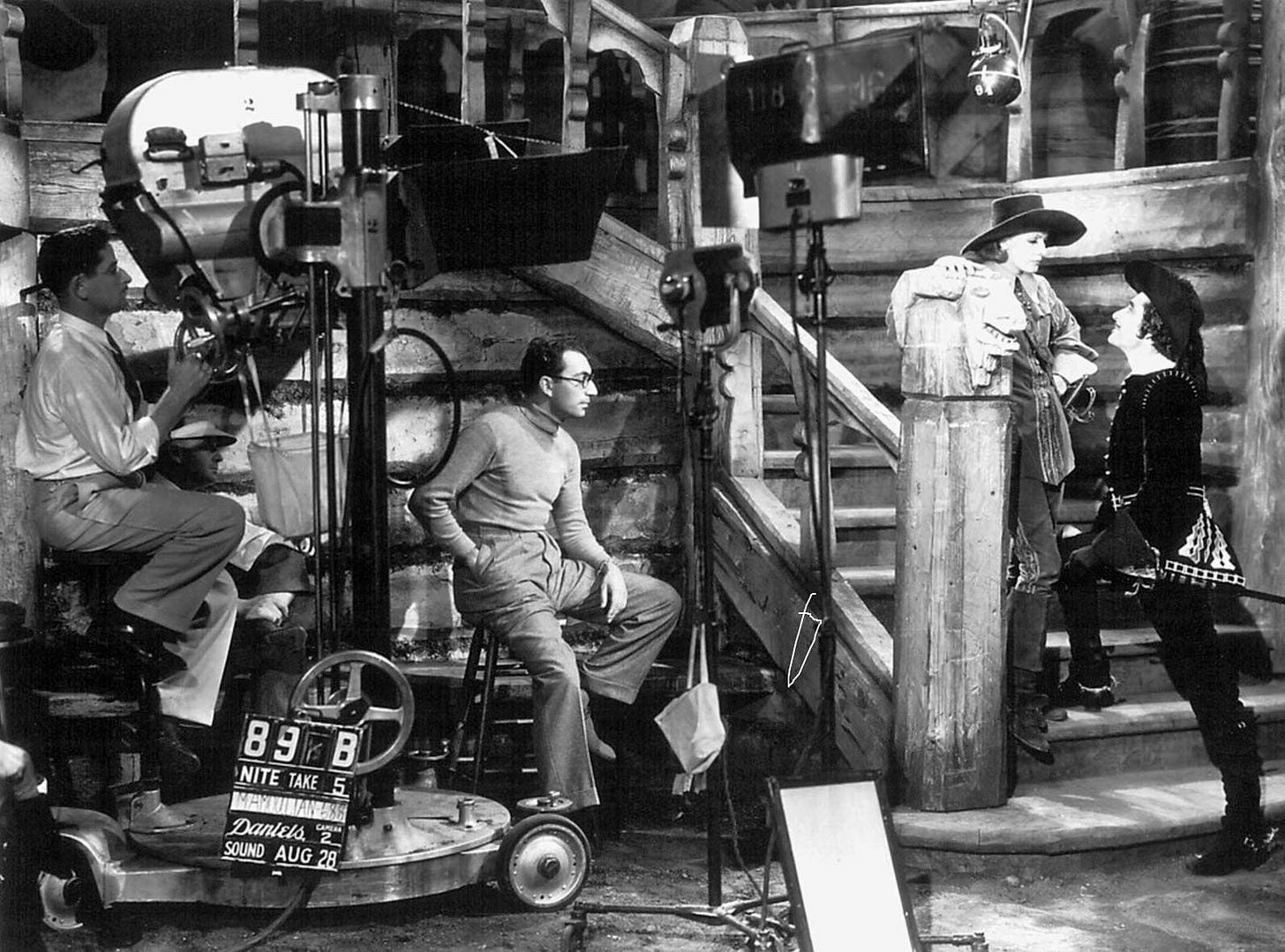

I particularly enjoyed the tales of his early days in Hollywood, working in Inceville as a supporting player, his tumultuous apprenticeship with Maurice Tourneur, and his first stabs at writing and directing. While he wrote several screenplays (and contributed writing work to several films in made later in his career), Jack only directed one film. The film was a star vehicle for Hope Hampton called Love’s Penalty (1921). While Jack called it “unbelievably horrible,” contemporary reviews praised his direction, with Photoplay going so far as to say there were “flashes of originality.” Joy told her daughter that it wasn’t a bad film and that Jack was his “own severest critic.” Clarence Brown, a friend of Jack’s from those early days, said he gave up too soon, telling Fountain, “Anyone can make a bad movie. I certainly did and I had six years’ experience on Jack. The difference is I was able to write it off and go on to my next assignment, while he couldn’t accept what he thought was a failure.” Unfortunately, the film is now considered lost so we can’t judge for ourselves, and although he always wanted to be a director, he never again stepped behind the camera.

Over the next few years, Jack found himself cast in romantic and heroic leading roles. Unfortunately, many of these films are also lost. His turn as Edmund Dantes in Monte Cristo (1922) was among those thought lost until it was found in an archive in the Czech Republic. Fountain asserts that Jack, “really didn’t care about the romantic lead business. Not even later. The more offbeat a part was, the better he liked it.” Despite his distaste for these romances, it is these films he is best known for today, and I think he brings a singularity to them, sometimes a darkness, sometimes quirky humor, that allows them to transcend beyond the average romances of this era. After the success of films like Victor Sjöström’s He Who Gets Slapped, Erich von Stroheim’s The Merry Widow, and his greatest triumph, King Vidor’s The Big Parade, Gilbert became known as The Great Lover. A designation that would ignite like nitrate film itself once he became paired with MGM’s new Swedish import: Greta Garbo.

Fountain’s book offers a lot of insights into the tumultuous relationship between Gilbert and Garbo, at least from his point of view of things. But while the public, then and now, cannot get enough of Gilbert, Garbo, and all of their drama, later in life Gilbert said Leatrice Joy was the actual love of his life. “She’s the one who really broke my heart,” he said. Fountain’s examinations of all of her father’s various love affairs is fascinating. She crafts a portrait of a man who is always looking for love, but pretty terrible at doing the work of committing to another person. I’m sure the pressures of building a career while always butting heads (and sometimes throwing hands) with your studio boss didn’t help things much either.

Oh yes, Fountain’s book makes a pretty good case that the decline of Gilbert’s career was orchestrated by Louis B. Mayer. Fountain traces the feud’s origins to a meeting sometime in 1926 wherein Jack pitched adapting for the screen a poem called “The Window in the Bye Street” by John Masefield. After outlining the plot, Mayer stated, “You can’t make a movie about a whore. A nice boy falling in love with a whore? What kind of movie would that make?” Jack pointed to Camille and Anna Christie as pretty good examples. Mayer then said only someone like Jack would think about bringing a whore into a story about a mother and son. Jack retorted, “What’s wrong with that? My own mother was a whore.” The possibly apocryphal story then goes that Mayer punched Jack in the face and later said that he hated “the bastard because he doesn’t love his mother.” By September of that year, Garbo had agreed to marry Jack in a double wedding with King Vidor and Eleanor Boardman. When she didn’t arrive on the day, Mayer is said to have remarked to Jack, “What do you have to marry her for? Why don’t you just fuck her and forget it?” Now it was Jack’s time to take a swing at Mayer. After his right hand man Eddie Mannix broke the two up, Mayer is said to have snarled, “I’ll destroy you if it costs me a million dollars.”

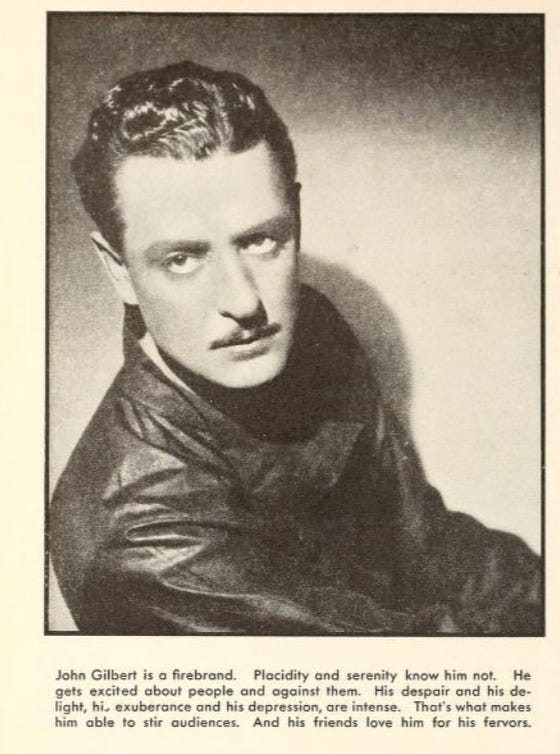

Over the next three years Gilbert would go on to make ten more feature films for MGM, becoming the highest paid star at the studio. He also clashed with Mayer at every chance. In May of 1928 a hatchet job of an article ran in Vanity Fair, in which the author Jim Tully, whose own hobo freight-riding days became the inspiration for Beggars of Life (1928), eviscerated Gilbert, writing, “His emotions are on the surface. His nature is not deep. His enthusiasms are as transient as newspaper headlines. He has no sense of humor. He struts his little celluloid hours upon the set like a youthful Hannibal.” The article then continues with a short biography, warping and distorting his traumatic youth. Jack reportedly threw up after he read the article. The editor of Photoplay later offered Jack the opportunity to set the record straight, printing his autobiography in a four-part series (which I linked out above.)

As the silent era gave way to the talkies, Mayer reportedly continued his crusade to end Gilbert’s career. This included contract clashes and assigning Gilbert to several less-than-stellar projects for his auspicious talkie debut: Redemption (1930) and His Glorious Night (1929), which was filmed second, but released first. Both films were directed by Lionel Barrymore, with whom Jack had an acrimonious relationship. While the lore is that Gilbert was laughed off the screen because of the sound of his voice, the truth is the sound recording on many of these early talkies was not great, and audiences often laughed in reaction to the strange newness of the technology. Jack’s voice was no Ronald Colman, but he sounded just fine. In fact, his ex-wife Leatrice Joy alway insisted he sounded like Joseph Cotten. Jo’s Virginia accent aside, I agree with that comparison.

Gilbert was determined to master the art of acting with sound. His third wife, the Broadway star Ina Claire, offered to help him with his enunciation. But according to Fountain her attempts did not go over well with Jack, who had mastered silent pantomime, but was now trying to not just learn how to speak on film, but also a whole new style of acting for the screen. While Mayer did his best to keep Jack in terrible films until his contract ran out, a few of these earlier talkies are incredibly charming.

The Phantom of Paris (1931), which is based on a story by Phantom of the Opera scribe Gaston Leroux, offered Jack the exact kind of complex character role he loved the best. In 1932 Iriving Thalberg helped revive a story Jack conceived of in 1928 called Downstairs (1932). He brought on Lenore J. Coffee and Melville Baker to punch up the script in which Jack plays a devious chauffeur named Karl who leaves a wake of destruction in his path after romancing and fleecing the women on staff at the house where he has just been hired and blackmailing his new employer’s wife. In the original version Jack wrote, the film ends with the scheming Karl killed in a vat of wine, but distributors complained and a new ending was shot with the mischievous Karl heading off for new misadventures with the idle rich.

In 1932, Gilbert was cast as the male lead opposite Jean Harlow in an adaptation of Wilson Collison’s play Red Dust (1932), then to be directed by Fred Niblo, who was later replaced by Jacques Feyder. However, screenwriter John Mahin suggested to the producer Hunt Stromberg that he check out a new actor he’d seen around the studio who was “built like a bull.” Stromberg was impressed with the young actor and Jack was taken off the picture, Feyder replaced with Victor Fleming, and the budget doubled. The film helped launch the career of that young actor, Clark Gable, who would become one of the biggest stars of the sound era.

In 1933, Garbo was set to star as the titular Swedish monarch in Queen Christina (1933), but was nervous on set. A young Laurence Olivier was originally cast opposite Garbo as her lover Antonio. After Jack appeared in costume for some screen tests to help relax Garbo, Olivier got the boot and Gilbert got the part. Olivier would later share, “I did the best I could in Queen Christina. I wanted the part very badly. Then I went to the studio and saw the tests. Here I am, supposed to be one of the greatest actors in the world, and this fading Jack Gilbert’s test was infinitely better than mine. It was perfectly obvious. They didn’t have to tell me.” For his work in the film, his penultimate role, Gilbert received some of the greatest reviews of his career.

His final film The Captain Hates The Sea (1934) was made for Columbia and directed by his longtime friend Lewis Milestone. The film was not marketed well and did poorly at the box office, but one critic noted that it was “boldly different” and called it the “absolute best neglected picture” from the last few years.

Jack spent the last two years of his life getting sober, mostly through the help of the unfailingly charitable Marlene Dietrich, who told her daughter Maria Riva that Jack’s “eyes are like coals — burning!” Recalling meeting him as a child, Riva wrote in her book Marlene Dietrich, “Talk about “burning goals”! You could get scorched being looked at by him! He had also a sweet, half-sad smile that could break your heart.” In her biography of Jack, Eve Golden shared some of the letters Dietrich saved from her time with Jack. In one he wrote, “Just because you are so sweet and beautiful and generous and fine. How nice a world if all people were like you.” Jack would often sign his letters to her “G.D.F.S.O.B.” which stood for “God Damn Fucking Son of a Bitch.”

During this time of renewed clarity and attempted sobriety, Jack also reconnected with his daughter Leatrice after she sent him a fan letter asking for a portrait of him that also enclosed a recent photograph of herself at camp holding up a fish. Touched by her correspondence, Jack asked her to visit if she felt ready. Over the course of the year, the two became close, visiting often and writing each other letters. In one letter to his daughter he wrote, “There really is a whole world out there, Tinker. A big and beautiful world. You can do almost anything. Anything at all.”

Jack was also plotting his next career move. In 1935, thanks to Dietrich, Jack was set to make his return to the screen opposite her and Gary Cooper in Frank Borzage’s Desire (1936). However early during the production, Jack suffered the first of several debilitating heart attacks. Paramount refused to take out insurance on him, ultimately replacing him with John Halliday. All that remains is some Technicolor test footage. Jack became too ill to even see his daughter on New Year’s Eve, and later died of heart failure early in the morning of January 9, 1936. He was only 38 years old.

In the years since his untimely death, Jack Gilbert’s reputation, like many of the great stars of the silent era, was twisted and warped. Rumors about his non-existent high pitched voice persisted. However, thanks to the efforts of film historians like Kevin Brownlow with his book The Parade’s Gone By and Hollywood: The Pioneers, the television series he produced with David Gill, Jeanine Basinger’s book Silent Stars, and the screenings of Jack’s films at film festivals around the world, broadcasts on TCM and subsequent releases on home video, the truth of his greatness — in both the silent and sound eras — remains undeniable. Films like Babylon will hopefully inspire more viewers to seek out his work as well. Just as recently as last summer footage of Jack in Flesh and the Devil was featured in Numa Perrier’s Netflix romantic comedy The Perfect Find.

Honestly, I recommend all thirteen films that are airing on TCM as part of their Summer Under The Stars tribute to Jack, but I figured I would recommend a handful that I particularly love.

Jack considered The Big Parade (1925) the pinnacle of his career. Directed by King Vidor, the film is notable both for its tender, understated love story between Jack’s American doughboy James and the French country girl Melisande (Renée Adorée), but also for its realistic and harrowing trench warfare sequences. Don’t let the film’s long runtime scare you away. You will be riveted! I have watched this film so many times and I get swept up in its sublime brilliance every time.

Erich von Stroheim did not want Jack to star in The Merry Widow (1925), going so far as to greet him on the first day of filming by saying, “Mr. Gilbert, I am forced to use you in my picture. I did not want you, but I will do everything in my power to make you comfortable.” Gilbert and von Stroheim eventually bonded over their shared difficulties working with star Mae Murray. The film became a critical and box office success. Of Gilbert’s performance, Robert E. Sherwood wrote, “Gilbert gives an eloquent, vibrant, keenly tempered interpretation of what might have been a trite romantic character. At every point he sparkles with brilliance and at times he bursts into flames.” My very simple take: John Gilbert hot.

I really love King Vidor’s Bardelys the Magnificent (1926), in which Jack plays a rakish marquis opposite Eleanor Boardman during the reign of King Louis XIII. MGM only had the rights for the novel, written by Rafael Sabatini, for ten years. In 1936 they destroyed the original negative and all known prints. For decades the film existed solely as a trailer and in an excerpt in Show People (1928), which was also directed by Vidor. Thankfully, in 2006 a nearly complete print was found in France (it was missing one reel), and the film was restored in all its glory. We had it briefly on FilmStruck back in the day and I made many, many GIFs.

Jack was not very fond of The Show (1927) because he had wanted to play the lead role in Liliom (the source material for the well-known musical Carousel). To spite him, Mayer instead had the writers department develop another Hungarian-set film for him based on another property the studio owned, the novel The Day of Souls by Charles Tenney Jackson. Regardless of Jack’s feelings about the circus-set project, he gives one of best dark and brooding performances, and modern audiences will of course get a kick out the weird touches of the singular auteur Tod Browning.

Jack worked with French starlet Renée Adorée on several films after they made a splash together in The Big Parade (1925), including Vidor’s La Bohème (1926), Browning’s The Show (1927), and The Cossacks (1928), a Tolstoy adaptation written by Frances Marion. The film’s original director George W. Hill was unhappy with the final product and wanted his named removed. Clarence Brown was then brought in for reshoots. I don’t know what the drama was, but Jack is really hot in this film and again has wonderful chemistry with Adorée. Two years later she contracted tuberculosis and died of the disease in 1933. She was only 35 years old.

I wrote earlier about Jack’s pet project Downstairs, so I’m just going to leave this GIF here to tempt to you to watch this deliciously dark pre-code dramedy, in which Jack has an absolute ball playing maybe the biggest piece of shit character of his career. Had he lived, he probably could have given Warren William a run for his money playing charming cads.

I am bummed TCM is not showing Victor Sjöström’s dark masterpiece He Who Gets Slapped, which features not only one of my favorite of Jack’s performances (he crafts hot hot hot chemistry with Norma Shearer), but also has what is, for my money, the greatest of Lon Chaney’s silent era performances. I said what I said. I also talked about this film in all its weird glory on the podcast A Very Good Year a few weeks ago as I extolled the virtues of 1924 as one of the great years for all of cinema.

Fountain ends her book with a story about a 1982 screening of Flesh and the Devil:

“For the first time I could remember, I saw his name in lights, over the marquee of a glittering movie palace, in one the greatest cities in the world. People were jostling in line for tickets, kids with punk haircuts and leather jackets nudging older women with white hair and little fur capes; Bessie Love was there and Charlie Chaplin’s family.

I stood with Kevin Brownlow and David Gill, who had engineered this event, watching the crowd. Suddenly, without warning, the tears I had been holding back for so many years came coursing down my cheeks. All the tears I couldn’t shed at his funeral, or even at his gravesite in Forest Lawn, or in the many movies of his I’d seen, came embarrassingly, like a river, and I found myself sobbing like a child on David Gill’s obliging shoulder.

It wasn’t from a sense of sadness, or loss for a father I loved, but because I knew then that Jack would always be alive. As long as there are movies, as long as people want to know how it all began — John Gilbert lives.”

I adored reading this. I'm definitely going to check out the films!!!