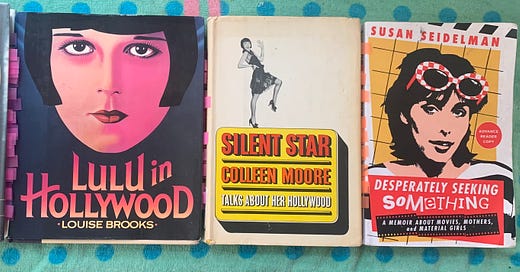

Obviously I have not posted a full reading recommendations post since last December, although I did do a post about the John Gilbert biography Dark Star during Summer Under the Stars in August. That doesn’t mean I haven’t been doing any reading though! I actually finished the books for this memoir-centric post before New York Film Festival in September …

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Cool People Have Feelings, Too to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.